-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

Aspen & American Music

Thursday, August 15, 2024

Posted By:Christine Goss

—

What constitutes American classical music is inextricably tied to the question of what constitutes America. Especially now, American classical music and the culture around it is characterized by its sheer diversity. When interviewed about the current state of new music and the AMFS’s role in this trajectory, Vice President for Artistic Administration Patrick Chamberlain explained: “the defining characteristic of [this Festival’s] commissioning profile is that there isn’t one.” The umbrella term “classical music” now ranges from rich, luxuriating neo-Romantic works by Jennifer Higdon to sparkling and angular pieces by Nico Muhly. And unlike most other countries for which there still exists an overarching, stylistic hegemony in classical music, American classical music is only becoming more wide-ranging. This diversity is directly fueled by the work being done at institutions like the Aspen Music Festival and School, where variety in conducting, performing, and composing is both allowed and encouraged to flourish.

Since its founding, Aspen has been a vessel for and wielded influence over classical music’s trajectory in the United States. An early example, among many others, was the 1953 world premiere of Julia Perry’s Stabat Mater—one of the first substantial world premieres of a classical work by a Black female composer from the United States. Situated in the heart of the American west—marked with the majestic landscapes that have inspired great works in nearly every artistic discipline—one struggles to think of a better place to make music. And for seventy-five years, many of the greatest musicians in the world have made pilgrimage here before going on to lead the American classical music legacy in all its multiplicity.

For example, Moscow-born Victor Babin came to the U.S. in 1937 and later was an AMFS music director. He went on to direct the Cleveland Institute of Music, where he was hugely influential in linking the CIM with Case Western Reserve University, two leading American music institutions. Eventually, Babin moved east to lead the Berkshire Music Festival at Tanglewood, continuing his affinity for summer music programs. Similarly, the Jewish conductor Joseph Rosenstock was in residence at the AMFS in 1953, having fled Nazi Germany in 1933. Just one year earlier, Rosenstock was the general director of the New York City Opera. In 1961 he returned to a conducting position at the Metropolitan Opera, after which he was appointed a regular member of the Met’s conducting staff until 1969.

But perhaps the most prominent association is with the famous French composer and member of Les Six, Darius Milhaud, who was in residence at the AMFS for fifteen seasons between 1952 and 1969. While in Aspen, Milhaud premiered his own works and influenced scores of young artists before becoming the honorary director of the Music Academy of the West in Santa Barbara. Both at Aspen and beyond, he mentored the next generation of composers, some of whom included William Bolcom, Philip Glass, Steven Reich, and Regina Hansen Willman, casting an undeniable influence on the American classical music scene.

This increasingly globalized and diasporic tapestry of influence is also evident in the AMFS’s educational initiatives. In addition to being a center of American music, the AMFS has become an internationally recognized classical music hub for young artists looking to reach new heights. This season, students from thirty-eight countries will return home and bring with them a piece of American classical music, after intense individual study, exposure to new compositional aesthetics, and collaboration with world-class and up-and-coming conductors.

When we talk about quintessential American music, many people immediately think of Copland’s Appalachian Spring, Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, or Barber’s Adagio for Strings, all of which have been enjoyed by AMFS audiences this season. And for as long as the Festival has existed, it has had a hand in bolstering that particular kind of the American classical music sound through commissions (Joan Tower’s Woman in 1993 and Philip Glass’s Four Seasons in 2010), world premieres (Bolcom’s First Symphony in 1957, Ives’s Chorale for Strings in quarter tones in 1974, and Augusta Read Thomas’s Ritual Incantations in 1999), and residencies (Roger Sessions ’63, Vincent Persichetti ’64, and David Diamond ’65). But as the Festival has grown, so has the institution’s understanding of how it must maintain its leading role in American classical music’s evolution. Across most classical music institutions in America, dominant narratives and power structures have preserved and perpetuated systemic inequities of many kinds. But while this may be a shared reality, it does not have to be an institutional legacy.

In recent years, the Aspen Music Festival and School has made significant strides in programming, student enrollment, and commissions. Just this season, audiences enjoyed works by Gabriela Lena Frank, a premiere by Aspen alumnus Joel Thompson, and the thoughtful African Queens recital given by Karen Slack and Kevin Miller, with newly commissioned songs from the seven-member composer collective, Blacknificent 7. In recent seasons, the Festival has crucially sustained activities and support for many composers and performers working to broaden the music that is considered American and classical: Béla Fleck, Jennifer Koh, Will Liverman, Missy Mazzoli, Jessie Montgomery, Brian Raphael Nabors, Nicholas Phan, Christopher Theofanidis, Chris Thile, Matthew Whitaker, Du Yun. This reparative and celebratory work aligns with the founding ideal of the Festival: a belief in the capacity of music to cross emotional, intellectual, and political boundaries, and to elevate the human spirit against all obstacles. All speak to the question President and CEO Alan Fletcher posed at this year’s opening convocation ceremony and which this season’s theme attempts to answer: who might we become and what might we achieve if we are all part of the conversation?

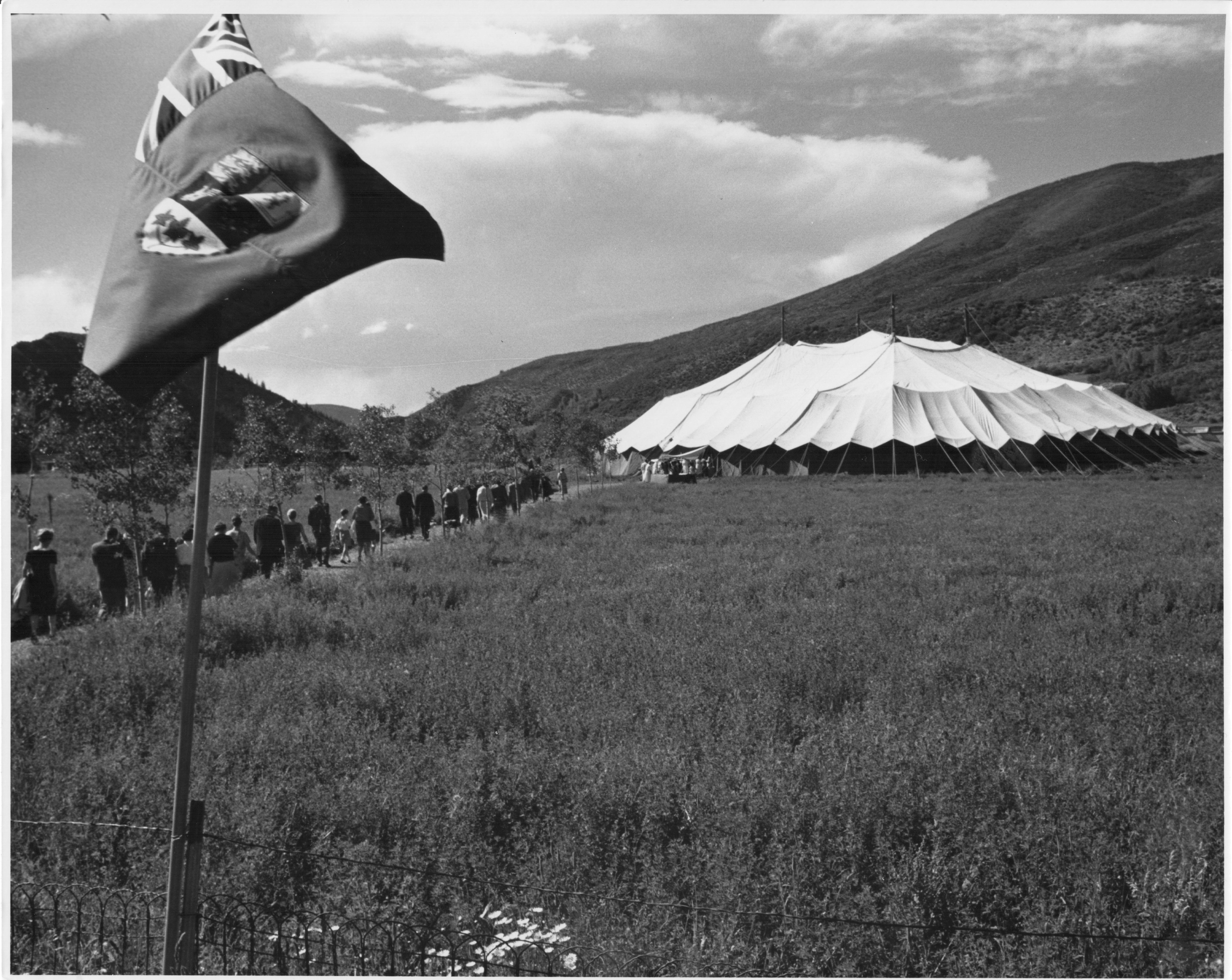

Image 0 Lead image: Saarinen Tent, photograph by Margaret Durrance.

Image 1: Darius Milhaud (left) and Olivier Messiaen at Aspen, 1962, photograph by Charles Abbott.

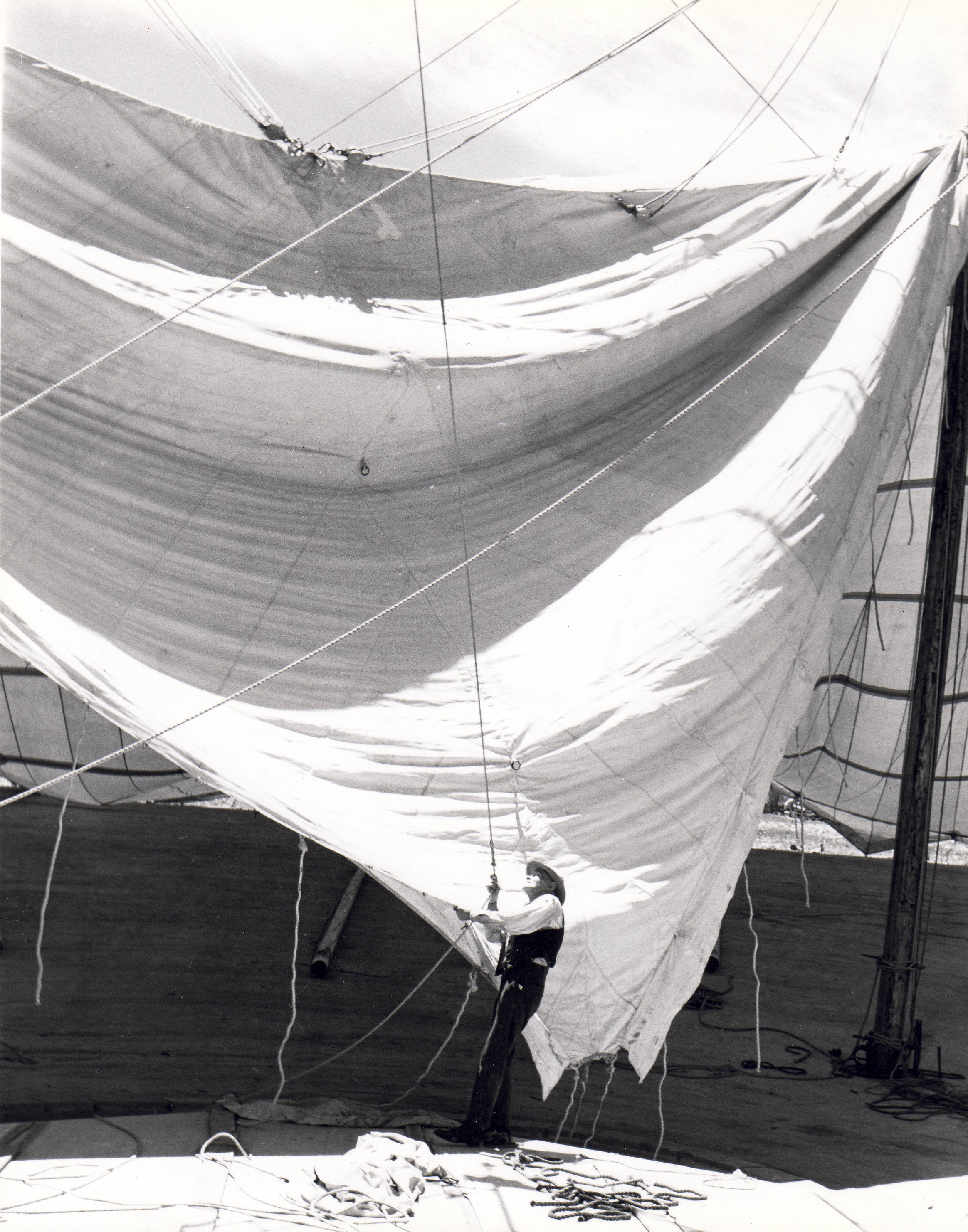

Image 2: Saarinen Tent raising, photograph by Margaret Durrance.

Connecticut native Christine Goss is the assistant program book editor for the AMFS and manager for Forgotten Clefs, a Renaissance wind quintet. She was research assistant to the New Isaac Edition’s general editor, cataloging thousands of notational variants from manuscripts and prints. She was also grant writer on a project resulting in a 2.5-million-dollar award endowing a new Lilly Library curator at Indiana University. Goss served eight years as an enlisted pianist in the U.S. Army Band. She now enjoys a civilian career as a jazz, church, and early music vocalist. Her research includes music cataloging, representations of sex and sexuality in choral literature, and twelfth- and thirteenth-century female troubadours. She has produced multiple concerts merging medieval and twentieth-century repertories, featuring masterworks alongside her own modern editions of medieval carols she arranged for female vocal ensemble. Goss earned simultaneous master’s degrees in library science and musicology at IU’s Luddy School of Informatics and the Jacobs School of Music.

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03