-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

Sounds of Pride: Queer Musical Identities, Histories, and Belonging

Friday, June 21, 2024

Posted By:Dr. Kristin Franseen

—

On the occasion of the “Sounds of Pride” celebration at the Aspen Music Festival, what is music’s role in shaping U.S. notions of queer identity across the twentieth and twenty-first centuries? How should we understand the tensions between the centrality of queer artists in “composing a nation” (to quote Nadine Hubbs in The Queer Composition of America’s Sound) and the difficulties of navigating public and private lives given systemic, institutional, and interpersonal bigotry, violence, and exclusion?

As we listen to Copland’s Appalachian Spring, recognizable nineteenth-century hymns might seem incongruent with Copland’s international musical training and cosmopolitan artistic community. Rather than exclusively acting as agents of socially conservative nostalgia, the markers of rural life emphasized in the Shaker hymn “Simple Gifts” and the ballet’s small-town revival setting make Copland’s musical America explicitly one that brings different and disparate voices together. Composed in 1944—in collaboration with choreographer Martha Graham for a ballet of the same title and arranged into the familiar orchestral suite the following year—Appalachian Spring found popular and critical success, earning Copland the Pulitzer Prize in Music at a cultural moment when questions of national identity were particularly fraught. In an early conversation with Copland about their collaboration, Graham recognized the tension inherent to this project, writing “I want to say things to people about themselves, some good and some bad . . . Sometimes the wall between is very thin.”

A hymn from a non-mainstream religious group that famously practiced celibacy may have been an odd choice for a statement on American musical identity; however, Shakers occupied an unusual place in the American popular imagination as both fringe outsiders and practitioners of a decidedly American folk tradition. Scholars have also observed that the Shakers’ communal living may have appealed to the composer’s leftist sensibilities. This representation of U.S. culture contains parallels with Copland’s generation of gay musicians: both the targets of oppression set apart from mainstream American culture, creating sounds and artistic paradigms that could increasingly be heard as “American.” In her study of Copland’s largely gay circle (including Virgil Thomson, Leonard Bernstein, Ned Rorem, etc.), Hubbs observes careful navigation of secrecy, privacy, mentorship, and collaboration, as well as references to established historical models for musical and social belonging.

This desire for history and community resonates as a theme in the music and careers of many twentieth- and twenty-first-century queer composers beyond Copland’s modernists. In the collaborative work Nutcracker Suite (1960; attributed to “Ellington-Strayhorn-Tchaikovsky”), composer-arranger Billy Strayhorn engaged with a musical past that not only crossed national and racial lines, thereby tying into postwar America’s fascination with musical crossover, but also suggested queer and gender-transgressive re-interpretations of Tchaikovsky’s music through re-contextualization and re-imagination. In a comment reprinted in Strayhorn’s biography, his friend Marian Logan framed the project in terms of a collaboration between him and the long-deceased Tchaikovsky, observing that “Strays liked to have a collaborator. He liked somebody to hide behind. Now he had the greatest collaborator of all time, a dead man.” A posthumous collaboration with Tchaikovsky gave Strayhorn license to explore different queer musical pasts, ranging from Tchaikovsky’s own biography to the early twentieth-century, queer Blues scene in New York City to Strayhorn’s own experiences as an openly gay Black man.

Experimental composer Pauline Oliveros’s provocative postcard series “Beethoven was a Lesbian” (1974), printed by photographer Alison Knowles, similarly draws ties between queer presents and musical pasts. Knowles and Oliveros contrast a bust of Beethoven with an image of Oliveros as “the composeress in her garden,” humorously challenging the problem of hidden queer knowledge and both sexist and homophobic bias in classical music. For Oliveros, the often exclusionary musical past represented by Beethoven’s canonical status served simultaneously as an object of parody, inspiration, and challenge. She is perhaps best known today for her development of Deep Listening and AUMI—experimental projects which seem at odds with traditional “works-based” approaches to musical composition and performance. In the same vein, she made consistent comment on the conventions underpinning the classical canon. In an interview with Martha Mockus, Oliveros remembered thinking of the postcards as a kind of comedic retort to the exclusion of women from mainstream music histories, saying “I thought it was really terrifically funny. Beethoven was a lesbian—let’s twist this thing around. If we’re out of the camp, then let’s turn it around.”

The three contemporary composers represented in this year’s “Sounds of Pride” series all use the past to say something about our current time and place. Bringing established tradition and new musical contexts together to provoke reinterpretation of the familiar pervades Alan Fletcher’s Three American Songs (2024), written for Renée Fleming and making its world premiere at this year’s Festival. Inspired by Copland’s song cycle Old American Songs, Fletcher sets the hymn “Wondrous Love” and folk song “The Cuckoo,” as well as Stephen Foster’s “Slumber, My Darling.” These reworkings of earlier texts and melodies provide space for an expanded understanding of themes of love, faith, and community across and beyond their original historical context and most immediate associations.

While Copland and Fletcher turn to pre-existing material to create their sonic ties and communities, Jihyun Kim and Matthew Aucoin blend longstanding literary musings on what it means to be and to belong in a society with new musical sounds. Kim’s Once Upon a Time… (2018), for Pierrot ensemble with additional percussion, is not an adaptation of any one existing fairy tale. In the words of the composer, “rather, general characteristics of fairy tale are portrayed in each musical scene,” with a wandering main motive getting lost only to find that “a sudden happy ending arrives in a most bizarre manner.” Mixing reality and unreality in fairy tale worlds—with their unlikely transformations, secret identities, and resistance to social expectations—has long held appeal for queer artists and performers. Such stories frequently present both hopeful models of escape from oppression and tragic resonances of the marginalized. As Kim observes, the sudden happy ending in Once Upon a Time… (as in all fairy tales) “depicts the nature of a story that not only is not true but could not possibly be true.”

Associations between identity, belonging, and looking to the past for guidance, however, is not always strictly idealistic. Aucoin’s Music for New Bodies (2024)—inspired by Jorie Graham’s poetry and Rachel Carson’s environmentalist writings, and based on a libretto compiled jointly by the composer and director Peter Sellars—asks us to consider not just the past and present impacts human beings, our societies, and our actions have had on the environment, but also what is at stake as we move into an unknown future increasingly defined by a fascination with the “post-human.”

All these works blend historical reflection with the potential for more inclusive, expansive, and progressive musical space. They each engage with the old and the new, representing transhistorical and genre-blurring approaches, and elevating the values of community and co-authorship. (Strayhorn in particular was known for “queer collaboration” in behind-the-scenes, creative arrangement and co-composition.) Taken together, their evocations of historical traditions should serve not just as nostalgic daydreams or celebrations of how far we’ve come, but as a reminder of how much work must be done to create an inclusive, just, and ethical world. It is worth remembering that, for all that Copland might be remembered today as the architect of an “Americana” sound, his output also included political songs such as “Into the Streets May First,” which actively advocate for collective social change.

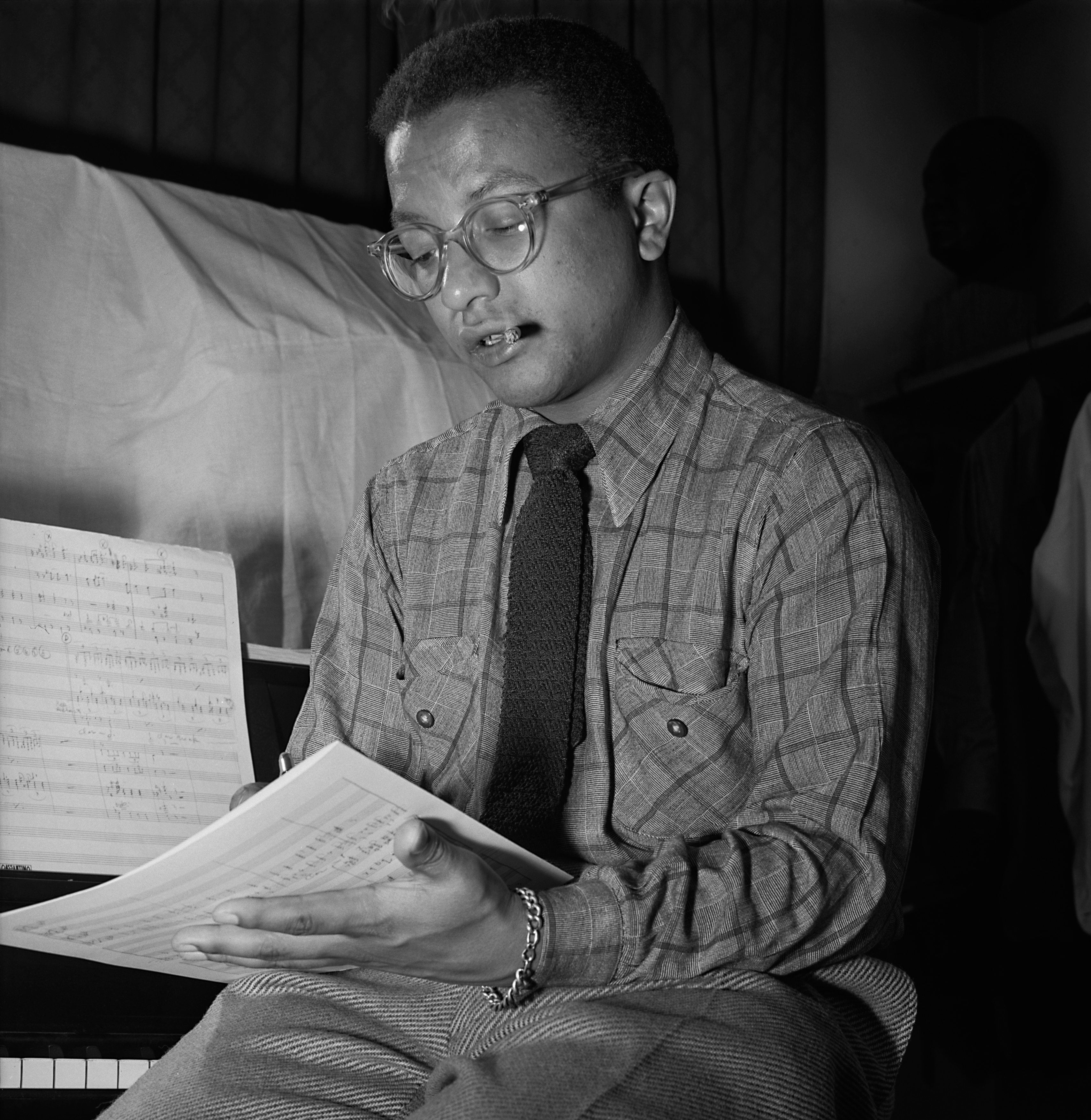

Pictured Above:

- First Image: Photograph of Martha Graham in Appalachian Spring.

- Second Image: Billy Strayhorn, New York, N.Y., c. 1947 (photograph) by William P. Gottlieb.

-----------------------------------------------------

Further Reading:

For more on Copland and modernism, see Nadine Hubbs’s The Queer Composition of America’s Sound (University of California Press, 2004). For more on Copland’s politics, see Elizabeth Crist’s Music for the Common Man: Aaron Copland during the Depression and War (Oxford University Press, 2005) and “Aaron Copland and the Popular Front” (published in the Journal of the American Musicological Society in 2003). For a discussion of broader representations of Shakers in US popular culture during Copland’s lifetime, see David VanderHamm’s “Simple Shaker Folk: Appropriation, American Identity, and Appalachian Spring” (published in American Music in 2018).

For Billy Strayhorn’s and Pauline Oliveros’s respective queer engagements with music history, see Lisa Barg’s Queer Arrangement: Billy Strayhorn and Midcentury Jazz Collaboration (Wesleyan University Press, 2023) and Martha Mockus’s Sounding Out: Pauline Oliveros and Lesbian Musicality (Routledge, 2007).

Sounds of Pride is supported in part by the National Endowment for the Arts.

Kristin M. Franseen is a postdoctoral associate in musicology at Western University, where her research focuses on the use of gossip, anecdote, and fiction as unreliable (if persistent) sources in music history and composer biography. Her first book, Imagining Musical Pasts: The Queer Literary Musicology of Vernon Lee, Rosa Newmarch, and Edward Prime-Stevenson, was published by Clemson University Press in 2023. Articles stemming from her research also appear in 19th-Century Music, Music & Letters, and Grove Music Online, as well as in the magazines VAN, Contingent, and Musique et pédagogie. Her current project, The Intriguing Afterlives of Antonio Salieri: Gossip, Fiction, and the Post-Truth in Music Biography, considers the interactions between fact, fiction, and semi-fiction in Salieri’s reception history from the 1820s to the present day.

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

03

-

-

03